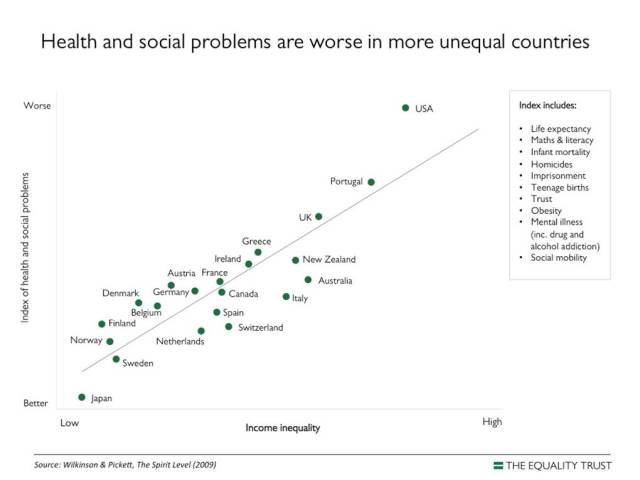

This blog started out as a record of my attempts to ‘escape the system’ and live more lightly and simply on the planet. Over time it’s become more focused on nature as a theme, and I’ve posted poetry as well as prose. The concept of fairness and equality has become more and more important to me in the wake of cumulative austerity policies, and the lack of challenge to them in mainstream media or political parties – until very recently.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that nearly three months ago I escaped the dismal political situation in Britain and moved temporarily to Sweden, attracted by its egalitarian reputation and large areas of wilderness. This post explores what it was like there, and what I’ve learned….

I’m travelling back to the UK after nearly three months in Sweden. My Blah Blah Car lift lands me in Brussels, the home of the European project. In one single afternoon, I hear and see more mentally-ill, aggressive, desperate and borderline criminal people than in the whole three months I’ve just spent in Sweden. I’m perplexed by the Metro, with its lack of staff, and overwhelmed by the city’s noise, cars, graffiti, smell of piss and the excrement in the streets. But it’s good, in a way, because I know this will toughen me up for returning to London.

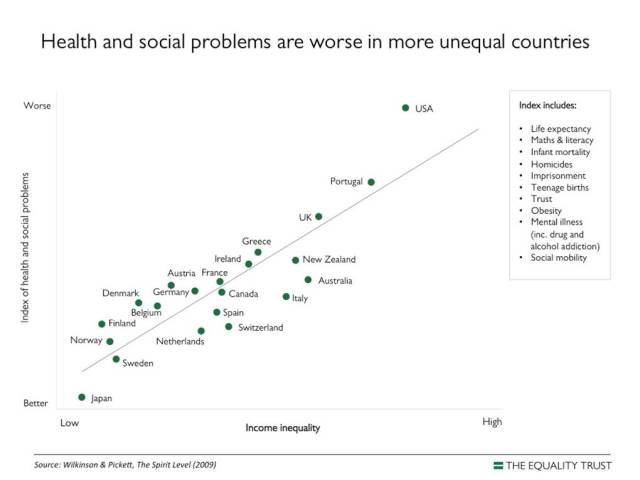

Most of my adult life I’ve heard about the higher levels of income and gender equality in Scandinavia, as well as its cleaner environment, lower crime rates and higher levels of trust. I wanted to experience the reality behind the statistics and find out what is it really like to live there. And, perhaps more importantly for a person coming from England: how do you create a fairer, better society? Does it have to cost more, does it entail losing a creative, competitive edge?

A parallel life

Over the past few months, helped by the disorienting effects of the midnight sun and the northern lights, I’ve played with having a parallel, Swedish life. Through the volunteering website Workaway.com I found myself several ‘jobs’ in different parts of Sweden – which gave me the chance to experience life in the north as well as the south of the country, both the countryside and the city. I lived with Swedish families, and I met some wonderful and less wonderful people. I embedded myself in local Swedish communities in a way no tourist ever can. I spent much of my time in the city of Luleå, not far from the Arctic Circle, but also spent time in Stockholm and the Uppsala area.

No paradise yet, but closer..

I didn’t find the perfect egalitarian idyll. Sweden shares some of England’s (and other European countries) issues, such as widening social inequality, refugees, obesity, race segregation, and unemployment. Like the UK, corporates have too much power, and the market culture has deformed public services (such as the state water company near-bankrupting itself by buying stakes in German nuclear power stations without bothering to tell anyone). On the whole though, I found the symptoms of these problems to be far less extreme than in the UK. So although I’ve noticed some examples of excessive wealth – such as Swedes parading themselves on huge expensive yachts, and a family where every child had its own speedboat – I found it possible to have a great quality of life here with little money.

High quality of life with little money

Sweden has a reputation for being expensive, but as far as I can see it’s mainly the alcohol, and apartments in Stockholm, that deserve this reputation. Don’t come here if you want to have a boozy holiday, that’s for sure. Accommodation is getting more expensive and harder to come by but it’s nowhere near the ridiculous levels in Britain. Nearly everything else which one relies on to navigate life- buses, trains, somewhere to study, places to relax, spend time with family – are affordable, subsidised, clean and accessible.

You can have a life here which is near impossible in Britain

What this means is that if you’re a student, creative person, or a parent, or a woman, or even a refugee (Sweden takes more refugees per capita than any other European country apart from Germany) – your life here will be completely different from that in the UK. Think about that. You’ll be able to do things, create things, that you’ll never be able to in Britain. I saw examples of this all the time.

inspiring view from KKV, a fantastic artist studio collective in Lulea

Support for creativity and families

For instance, an artist couple I met in Luleå are able to combine being part-time artists with bringing up their son. The fact that they are artists, and part-time ones, means they do not have a lot of money. But thanks to a rent-subsidised apartment (roughly £320 per month) and an incredibly cheap, stunning cooperative art studio containing state of the art facilities (less than £100 per year) and subsidised child care (£53 per month) they can practice what they are good at, look after their son, and even have time and energy to enjoy themselves.

![20150804_154707[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150804_1547071.jpg?w=640)

The large studio space available for hire at KKV – looking out onto forest

printing room at KKV

Compare that situation with Britain. I know so many parents where one partner finds that they have to work longer hours or take on a more stressful job to cover the cost of losing an entire income whilst the other parent looks after the child. Or mothers who go back to work and find that a huge proportion of their salary goes straight out again to cover the childcare costs. This creates stress. Stress on the person having to work harder (usually the man) and therefore see less of their children, and stress for the person sacrificing their career to look after them (usually the woman). Stress for the child, whose parents are too tired to enjoy them. It’s sad for all of them, and it probably leads to a few marital breakdowns along the way.

![20150802_135157[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150802_1351571.jpg?w=300)

Another affordable great art coop in Lulea with affordable artist studios

![20150802_132050[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150802_1320501.jpg?w=300)

Another artist coop with beautiful affordable studios

Even those artists or writers I know in Britain who don’t have children often have to work in other jobs part-time just to ensure they have enough money to live on. They have to find a way to fit the creativity in around their job. And of course that means they’re often too tired or busy to develop their art.

Gender equality

One of the things I noticed in Brussels on my return were huge advertising posters of women’s breasts, not even bothering to include a head. This kind of image was entirely absent in Sweden, where there are three women party leaders in parliament, two of whom have had babies this year and are sharing their parental leave.

Swedish fathers can take months off work to look after their children or leave the office at 4pm to pick them up from school, Maddy Savage points out, editor of the Local Sweden, an English language news website. And because sharing childcare is normalised, so is the idea of having both men and women in senior jobs, regardless of whether they have kids.

Most Swedish women I met seemed very practical, confident, grounded people. We all know how to get a fire going and forage for food, they told me – at least in the north of Sweden. And travelling at night on public transport felt very safe as I noticed lots of other single women doing the same. I also noticed the widespread coverage of women’s sport in local newspapers and on TV; it’s taken seriously, unlike in Britain.

Swedish women doing their practical thing!

Foraging for wild raspberries

Free education

Although I already have a degree, I’d love to take another high level course of study – but I know that doing so will involve a large sum of money, which makes me think twice, and delay while I find ways to save the cash. But if I lived in Sweden, I’d get to study for free.

In my parallel life as a Swedish citizen I would be much more highly skilled and better-educated than I am now. And it shows – Swedes have a track record for innovation. I didn’t realise til I came here that Skype and Spotify are Swedish inventions, and that the country produces more patents a year than any other. The World Economic Forum recently voted them the seventh most innovative economy in the world due to the amount Sweden spends on education, alongside infrastructure and R and D.

Sweden gives the lie to austerity

This shows how the austerity policies in Britain have nothing to do with economics and everything to do with ideology. Sweden invests in its public sector, its infrastructure and yet has weathered the recession better than the UK. Whereas in England we’re told that if we want to be competitive we have to hammer the public sector and cut costs.

Sweden’s large public sector and high taxes doesn’t seem to have put off business- Facebook has its only data storage facility outside of the US in Luleå. The public sector in Luleå employs over 7,000 people, according to its tourist handbook (numbers like this wouldn’t even make it into an English tourist handbook) for a population of 75,000. I googled the numbers of public sector employees for Lewisham, where I live in London. With its population of 286,000, over three times the size, they employed under 3,000 employees. Where would you rather work?

Disposable income not needed

If you’re a student, or a creative person in Sweden, or a lower-paid worker, you likely won’t have a lot of disposable income, but that doesn’t matter so much here, because so many great, well-maintained facilities are free, or subsidised. That’s partly why Swedes who’ve previously lived in India or London tell me that they mix more with people from different backgrounds now – in Sweden there’s less of a social divide between a hairdresser and someone with a pHd. Greater income quality, less consumerism and shared, appreciated, public resources make this happen, but underlying this are the Scandinavian concepts of ‘Lagom’ and ‘Jantelagen’.

Lagom- Just enough

Folk myth says that the Lagom ‘just enough’ concept came from the Viking practice of sharing out mead fairly among the crew, but whatever its origins it underpins the Swedish psyche, behaviour and what I felt in Sweden – a sense of cohesion, of things working well, and working for everybody. ‘Just enough’ offers a sustainable alternative to the hoarding ‘more, more’ pressures of consumerism. In Sweden it is still considered ideal to be modest and avoid extremes, a welcome change from the prevailing competitive culture of the individual which, post-war, has spread throughout the Western world (see NYT Bestseller Quiet by Susan Cain for more on this).

Jantelagen – it’s ugly to think you’re better than anyone else

I have never heard anyone in Sweden bragging at length about their accomplishments. And I met a lot of people who were very good at listening. Even when I attended a party to launch a new book, the hosts who’d written the book spent much of their speech thanking their guests and those who’d helped them write it.

Jantelagen is a Scandinavian concept advocating societally-enforced humility. It discourages people from promoting their own achievements over those of others. Viewed negatively, it discourages individual effort, but viewed positively, it keeps egos in place, boosts self-esteem and reduces stress. I certainly didn’t notice it hampering the individual creativity of many of the many artists I met and worked with in Luleå. Perhaps it just means you can spend more time creating and less time having to market and sell yourself – a relief, if you ask me.

The Swedish Commons

So what are these great well-maintained facilities? I booked a night train at the last minute all the way from Stockholm to the Arctic Circle, with a nice bed for the night – for about €60. The trains are safe, and clean. Free wi-fi at every railway station meant I could surf the net for free most of the time. Buses were fairly cheap in Luleå; and best of all I found I could cycle everywhere, without risking life and limb, thanks to ubiquitous cycle lanes. It also felt far more pedestrian-friendly.

In Luleå, when it got too cold to swim outside, I went to the beautiful state of the art swimming pool and super-hot sauna – it cost me 40 SEK, which is less than four English pounds.

The concept of the ‘commons’ is important. Even relatively expensive apartment blocks have communal washing machines, freeing up space and saving money. Yes, this can lead to arguments between neighbours, but it also means Swedes get good practice in finding consensus. My friend in Stockholm, who owns her own flat, tells me that she and all the other residents make all the communal decisions about the block – they have to work cooperatively to get things done, rather than farming out these decisions through an external housing association, like where I live in London. Her resident association agreed to install a communal sauna in the block, which meant I could enjoy a free sauna during my stay.

![20150805_124212[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150805_1242121.jpg?w=614)

you get paid to recycle some items in sweden – another example of swedish pragmatism

![20150805_113437[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150805_1134371.jpg?w=300)

But the UK is fairer in some ways

I don’t want to suggest that everything in Sweden is perfect. The far right Swedish Democrats are doing well in the polls. One thing I’ve noticed where Sweden is less egalitarian than the UK is going to see the doctor and getting free access to museums and art galleries. Although it only costs a nominal fee to see the doctor ( approx £16) this was enough to deter me making a follow-up visit towards the end of my stay when funds were low. Sweden started charging for doctor´s visits when it carried out its programme of cuts in the 90s, and I suspect has created widening health inequalities. Most of the art galleries and museums in Stockholm charged for entry, I also noticed, which meant I didn’t visit as many. However, Lulea’s impressive Kulturhus had many free exhibitions, events and affordable concerts, so the picture is mixed.

Still a cohesive community

Despite the recent popularity of the Right wing party, most Swedes I’ve spoken to are proud of the fact that it’s possible for anyone in Sweden to have a great quality of life, irrespective of income. They don’t moan about paying their taxes to support people who work supposedly less hard, like I hear in Britain – they feel that they share in the bounty their taxes provide, like free education.

No long hours culture

Maybe they’re more community-minded because they don’t have to work so hard. Here, people tell me it’s unusual for people to work more than 40 hours a week – working more doesn’t earn you brownie points, it’s more likely to make people think you’re anti-social. Taking regular fika breaks for tea and coffee with your work colleagues is important social glue.

Some companies in Sweden are now experimenting with a six-hour working day, reporting greater efficiency, less conflict, happier staff. Then there’s the generous maternal and paternity leave – parents are entitled to 480 days of parental leave when a child is born or adopted, getting the equivalent of 105 euros a day. Imagine how much easier life would be if we had that, combined with the Swedish virtually free child care, in Britain.

Fences still low

There was talk a few years ago about Swedes emulating the US and UK and embracing the concept of ‘gated communities’ but I’m pleased to report I haven’t yet found one. What I have found is that the fences around properties are still really low, and that even in rich areas it’s common for the main back doors of apartment blocks to be unlocked.

Trust

Surveys show that Swedes have one of the highest levels of trust in the world, and I think this attitude permeates all the positive things I notice here. Trust has enabled the generous welfare state to work, and the ensuing great quality of life encourages more trust – a virtuous circle. Everywhere I see examples of this trust; for example municipally-maintained fire pits in densely wooded areas, or in the middle of towns. In Luleå on a Friday night by the docks, I enjoyed glowing lights of fires, manned by groups of teenagers. They were expected to light fires, encouraged to do so and trusted to look after them.

these glowing lights are from cosy fires tended by groups of teenagers

Another thing I noticed was axes left everywhere. People would totally freak about this in the UK. An axe had permanent residence beside the ubiquitous fire pit in the back garden of my friend’s place, an apartment block where several children lived. I remember watching a five-year-old carve her likeness out of a branch using a sharp Mora knife, her mother barely supervising – this was obviously something she did regularly and could be trusted with.

My Swedish friend allowed her kids, aged 5 and 7, to roam independently in the local area, and said this was a fairly common attitude ( British children have far less personal freedom to roam independently than their European peers, largely due to traffic and stranger-danger fears). A Stockholm metro worker loaned me his state-of-the-art Apple Mac laptop when I needed to book a hostel.

Come and sleep in our cathedral

When I got to Stockholm and visited the famous church in Gammelstan I was very tired, having taken the night-train (cĺean, safe, well-used) from down south. So with what I see now as typical Swedish pragmatism, the woman on the desk and the priest tour guide invited me to sleep in the church. Can you imagine that happening in Westminster Abbey? They’d probably call the police. The pew was a bit hard, but I had a great nap that afternoon, awaking refreshed and able to enjoy the tower tour and fantastic views over the city.

An example of the swedish relaxed attitude: am I imagining it, or has this guy got his hands in his pockets ?

Life is less of a struggle

Statistics tell me that Sweden has lower crime rates, but I saw that for myself, at least low-level crime – Swedes have no truck with large cumbersome bike locks. Many bikes come with a built-in, small mechanism on the wheel which takes a second to lock and unlock, and some people don’t bother even using those.

All these things add up, and affect your quality of life. Here life seems far less of a struggle, even down to the small detail of not having to carry a heavy lock around with you and spend unnecessary amounts of time locking and unlocking your bike.

The Natural Commons

But I’ve saved the best, accessible, affordable, communal ‘resource’ til last – nature. This is where I spent most of my time, walking, swimming, boating, picking berries, star-gazing, cooking over fires, watching the Northern Lights. Even in Stockholm, I went for an early morning swim naked off one of the islands, yards from a petrol station, and picked wild mushrooms from nearby woods. And when you’re cooling off from a wood-fired sauna naked as a baby in a crystal clear sea, the world of consumerism just pales into insignificance. ( I want to write more about Swedish nature in my next blog post).

Swedes have codified their love of nature into law through the Allemansrätt. Unlike Britain, this means you can walk, swim, boat and pitch a tent anywhere, even on private land, so long as you can’t be seen from the house. Picking berries and fungi are important seasonal pastimes for many Swedes, and I got involved in mushrooming, blueberry picking and searching for elusive cloudberries. And I think this love of nature, as well as the welfare state, is what roots the trust and the pragmatism I saw all around me.

All in all I’ve seen a society which is still working well, despite the privatisations and cuts which took place here in the 90s. I’ve not found a panacea for climate change, unsustainable growth, corporate dominance, the end of cheap oil; but I can see that Sweden, like other Nordic countries, is managing the transition to the new order much more gracefully. Next time, I want to visit Norway and Finland. Norway consistently tops social equality polls and Finland has even mooted the idea of Basic Income.

My experience has invigorated my belief that a better life is possible for people living in Britain (and Sweden), if we can finally overthrow the poisonous neo-liberal legacy of Thatcher. What kind of life would you like you and your children to lead? Ask for it. Demand it. Because, not so many miles away, I’ve seen that it’s still possible.

![20150804_154707[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150804_1547071.jpg?w=640)

![20150802_135157[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150802_1351571.jpg?w=300)

![20150802_132050[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150802_1320501.jpg?w=300)

![20150805_124212[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150805_1242121.jpg?w=614)

![20150805_113437[1]](https://simplyradical.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/20150805_1134371.jpg?w=300)